From the Western feminist movements of suffrage during the 19th and early 20th centuries, liberation during the 1960s, and the recent developments focused on diversity, individuality and responses in the recent decades till date, the concept of womanhood has changed in the eyes of various societies over the years. While there is still much to discuss and share in most contemporary societies today, the Western experiences of feminism cannot be held as the sole voice and perspective for women in a world filled with diverse cultures and histories.

When we focus on China and its long history and deep cultural heritage, it is evident that women’s status and societal definition have been in flux due to societal and political ideology changes throughout the ages.

Perhaps the most commonly subscribed precepts of the role of women in pre-Modern China[1] would centre on the Confucian Three Followings and Four Virtues 三從四德 that women are to follow and obey the man of their household – her father when she is a youth, her husband when she is married, and her son when she is widowed.[2]

However, the status and roles of women began to change with the New Culture Movement (1915—1921) and the Communist Revolution’s (1921—1949) ideologies that encouraged the enlightenment and elevation of women by subverting pre-Modern China’s patriarchal ideologies in Modern China.

Between ideological and political perspectives and tensions on Chinese women, stories of historical or folklore women captured our imagination over generations. For example, the Northern and Southern dynasty’s Hua Mulan 花木兰, Tang dynasty’s Empress Dowager Wu Zetian 武則天, Ming dynasty’s Lin Siniang 林四娘, Qing dynasty’s Empress Dowager Cixi 慈禧太后 and Qiu Jin 秋瑾, Lu Xun’s depiction of Xiang Lin’s Wife祥林嫂 in The New Year’s Sacrifice (祝福, 1924), the Song Sisters 宋氏三姐妹 and many more. Their stories explored concepts of affection, power, resilience, sacrifice, survival and virtue. These female figures in history and folklore share a common thread of tying events, people and places together – being the conduit for society, culture and intergenerational relevance.

Let us take a moment to consider the importance of women, as a focus, in our lives from more uncomplicated and perhaps general sweeping points of view.

The maternal connection between child and mother begins with conception – an irreversible bond between women and their offspring. The nourishment from the mother does not just centre on the physiological needs of a child but includes the education and upbringing aspects as the child grows up.

The words that the mother speaks to the child, the behaviours shown to the child and other aspects of maternal guidance significantly influence the development of a growing child. Even if we do consider the variances of maternal interactions, the earlier mentioned irreversible bond between mother and child can never be negated.

When we consider the aspect of men in women’s lives, it goes beyond the microcosm of a family unit to between men and women in terms of relationships of societal roles or companionship.[3] Similar to reality, it could also be highlighted that men sought female companionship in countless tales found in Chinese folklore and historical narratives.

For example, Cao Xueqin’s 曹雪芹 Dream of the Red Chamber 红楼梦 explores protagonist Jia Baoyu’s 贾宝玉 stories and relationships with the women within his household. While we can view Dream of the Red Chamber as delving into the themes of romantic love, material wealth, power and philosophy,[4] it should be noted that the story would not make sense without the women characters’ existence. These women form the conceptual conduit that allows the telling of Cao Xueqin’s observations on his era’s aesthetics, lifestyles, social relationships and world perspective.

From stories of children and their mothers, women’s societal roles and stories of companionship, it is evident that women form a formidable sociological conduit for every member of society and across generations.

Perhaps as an allusion to women as a sociological conduit, Dorothy Ko described 17th-century Chinese women writers as “teachers of the inner chambers”. Be it written communications, paintings and even roles in literature, women have eventually transcended their supposed interior spheres to influence individuals outside and beyond their time, to continue to hold societies together across time.[5]

However, it should be noted that such sociological relevance is not a generality that can be applied to every Chinese person. Still, such relevance can be incredibly influential for those brought up in this diverse and rich Chinese heritage and culture.

This rich cultural environment is perhaps how and why, in one particular circumstance, an artist reverently views women for their significance and virtues in society.

Zhao Hong as a New Literati

Born in Beijing in the 1960s, Zhao Hong 赵宏 completed his university studies in 1990 and became a university lecturer soon after. Zhao is deeply passionate about ancient Chinese artefacts and culture, and devoted tremendous efforts to exploring classic Chinese history and literature.

Since 2001, Zhao Hong became intimately involved in cultural and heritage conservation roles in China, where his involvement with the official recovery of the lost Yuanmingyuan Bronze Zodiacs 圆明园十二生肖兽首铜像 was a significant highlight in his career. In 2011, he moved to Singapore to chart a new course in his life.

Since his youth, his father nurtured Zhao Hong’s love for Chinese calligraphy, ancient Chinese literary works, paintings and culture. Under the mentorship of Professor Guo Xiaohuan 郭晓川,[6] Zhao was exposed to modern Western art history and contemporary ink practices when he was the Deputy Director at Today Art Museum 今日美术馆, located in Beijing.[7]

By adopting a New Literati perspective, Zhao Hong contemporises classical Chinese philosophy and painting with emotions, objects and subjects from today’s daily life and society. Zhao opines that a deep understanding of Chinese literary classics and painting is an essential foundation for a contemporary artist of relevance in today’s society.

If there is no conscious awareness of the past, the creations of today as modern or even contemporary would be challenging to position or present to audiences. With the knowledge and understanding of the past, an artist can make confident breakthroughs in artistic practice and philosophy.

Xiaomeirentu小美人图

In his xiaomeirentu 小美人图 [Images of Womenfolk] series, Zhao Hong casts the women in his paintings as the central conduit of society. While the traditional patriarchal system of inner and outer spheres for women and men had its roots in Confucian philosophy, Zhao emphasises the social interconnectivity women have within society.

Zhao Hong holds the perspective that women often serve as a keeper of familial and social connections, where womenfolk can transmit the awareness of who an individual is, who the individual’s father is, familial ties between individuals, and familial histories across generations.

Additionally, Zhao points out that womenfolk’s roles within families and society are significant and multifaceted – their participation as economic contributors, nurturers and educators of the young, and as guides for members of today’s society.

Zhao opines that womenfolk are the key to familial bloodline continuity. In traditional Chinese practices, the continuity of a family surname is linked to the family’s males. However, womenfolk are a necessity towards that end as a single male will not be able to further the familial surname on his own.

Hence Zhao Hong’s perspective of the centrality of womenfolk, as an essential societal conduit, is a different take on the perceived patriarchal emphasis on men.

Zhao Hong credits his approach to the subject of womenfolk in the form of meirentu 美人图 [Paintings of Beautiful Women] to two prominent contemporary Chinese artists, Zhu Xin Jian 朱新建 (b. 1953—2014) and Li Jin 李津 (b. 1958). Zhu and Li have been considered part of the New Literati movement in China, emphasising the juxtaposition of poetic Chinese calligraphy and painting with contemporary thinking.

Zhu Xin Jian’s approach towards women developed from the pictorial lines of Chinese folk opera to the emotive renderings of beautiful women. Zhu’s Chinese ink paintings of beautiful women are poetically sensual, often adapting the usage of classic poetry to give a modern reading through his character painting.

Fig. 1 Greyscale detail of artwork from the catalogue of Zhu Xin Jian 朱新建, Rensheng De Gentie: Suibianshuoshuo 人生的跟帖: 随便说说. Nanjin 南京: Jiangsu Meishuchubanshe 江苏美术出版社, 2006, p 129.

Li Jin’s “life is a feast” approach borders on the hedonistic aspects of modern thoughts and lifestyles. The intense intimacy of women, men, carved meat and other luxurious dining items are overwhelming in Li’s presentation – his calligraphy is crude and powerfully written as if the words were made drunk in a hedonistic haze.

Fig. 2 Greyscale detail of artwork from the catalogue of Li Jin 李津, Xinluji – Li Jin 心律集 – 李津. Beijing 北京: Renminmieshu Chubanshe 人民美术出版社, 2016, p 159.

Li’s depiction of women, befitting the avarice of hedonism, is sexual, provocative and or complementary to the cuisines laid on his tables. It is also to note that Li’s subjects are often depicted in such proximity, implied from his constant self-insertion in his artworks, that one can almost smell the sweat and various aromas.

Zhu Xin Jian and Li Jin’s treatment of womenfolk in their meirentu exemplifies women’s physical attractiveness and the pleasures of admiring such women from perspectives of sexual attraction and enjoyment.

Inspired by Zhu Xin Jian and Li Jin’s frankness in their emotions and thoughts, Zhao Hong sought to approach the theme of womenfolk from a respectful distance of admiration instead.

Zhao Hong’s perspective of womenfolk as a sociological conduit can be seen in various presentation approaches through poetry, song lyrics and personal musings in his paintings.

Zhao emphasises the relevance of womenfolk in modern society through the context of the written text – be it social relations, commentaries on current situations, or audience interpretations based on their own emotions and experiences.

Zhao Hong establishes the depicted womenfolk as contemporaries by the inclusion of in-trend accessories and designs (for example, coloured contact lenses, jewellery, pets and textile patterns) alongside chic modern ethnic clothing and hairstyles – all of which compounded and synthesised with an established knowledge of brushwork and modifications to traditional painting styles of women in pre-Modern China.

Fig. 3 Detail of Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 as seen in Hongloumeng tuyong 红楼梦图咏, 1879.

The engraving is accredited to Huaipu Jushi 淮浦居士.

Zhao Hong’s signature artistic narrative is the quiet and respectful juxtaposition of contemporary elements with his womenfolk. The visual distance and perspectives, narrative angles and texts suggest Zhao’s deep admiration of the elegance, refinement and virtues found in his womenfolk subjects.

Fig. 4 Lloyd Zhao 赵宏, Renshengrumeng wozhenqing 人生如梦我真情, 2021, Chinese ink and colour pigment on rice paper, 34 x 17 cm. G Art Gallery, Singapore.

人生如梦,我投入的却是真情。世界先爱了我,我不能不爱她。

Though life is more of a dream, I take it seriously, and truly, the world has given love to me, how cannot I stop loving her?

— Translated by Zhao Hong

Adapted from Wang Zengqi’s 汪曾祺 writing in Renjian caomu 人间草木 [Beauty among Us], Renshengrumeng wozhenqing 人生如梦我真情 [Life is like a Dream, and Sincere is my Love] reminds us to remember cherishing and loving whatever that has lent themselves to the creation of us as individuals.

With Zhao’s inclusion of an elegant-looking woman as a pairing with the text, the role of motherhood of womenfolk, as the source of creation and maternal love, allows us to focus our love and respect towards can thus be interpreted and appreciated.

Another perspective of the elegant-looking woman could be seen as a companion of an individual who has received her attention and love, thus admitting that it would be unfair and unjust if the attention and love were not mutual.

Fig. 5 Lloyd Zhao 赵宏, Duokanniyiyan 多看你一眼, 2021, Chinese ink and colour pigment on rice paper, 34 x 17 cm. G Art Gallery, Singapore.

只是因为在人群中 多看了你一眼

It is all because I have taken another look at you in the crowds.

— Translated by Zhao Hong

With words borrowed from Faye Wong’s 王菲 1994 song Chuanqi 传奇 [Legend], Duokanniyiyan 多看你一眼 [Another Look] represents the attraction of a woman that garnered itself a second look in the hustle and bustle of city living. Perhaps utilising the cover of the crowds, a shy individual was thus able to appreciate the subjective beauty of a woman. It should also be noted that the visual distance and implied crowds suggest a respectful admiration of womenfolk instead of desires.

Due to the second look, the artwork’s text suggests that the woman in question might have noticed the shy individual. This development also implies that a conversation might have started between the two, or the woman might have sparked a romantic motivation for the shy individual. These narrative implications indicate the centrality of womenfolk as a key component to the firing of imaginations and motivations.

Fig. 6 Lloyd Zhao 赵宏, Shenshen de ningwang nidelian 深深地凝望你的脸, 2021, Chinese ink and colour pigment on rice paper, 34 x 17 cm. G Art Gallery, Singapore.

深深地凝望你的脸,不需要更多的语言。紧紧地握住你的手,这温暖依旧未改变。

Staring at you with deep love, no more words are needed. Holding your hands tightly, the warmth remains unchanged.

— Translated by Zhao Hong

With a soft but penetrative gaze, Shenshen de ningwang nidelian 深深地凝望你的脸 [Gazing Deeply into Your Face] speaks of the love a couple has for each other. Adapted from the song Qingqingde pengzhennidenian 轻轻的捧着你的脸 [Gently Holding your Face],[8] the artwork brings to mind the non-verbal communicative aspects of two individuals who are in tune with each other due to their relationship.

It can also be interpreted as a platonic relationship between friends where words are sometimes not required to convey feelings of concern, chemistry and respect for each other. Including a woman in this line of thought brings to mind the general ease most would feel when interacting with women, such as interactions in social, retail, education, healthcare settings and many more.

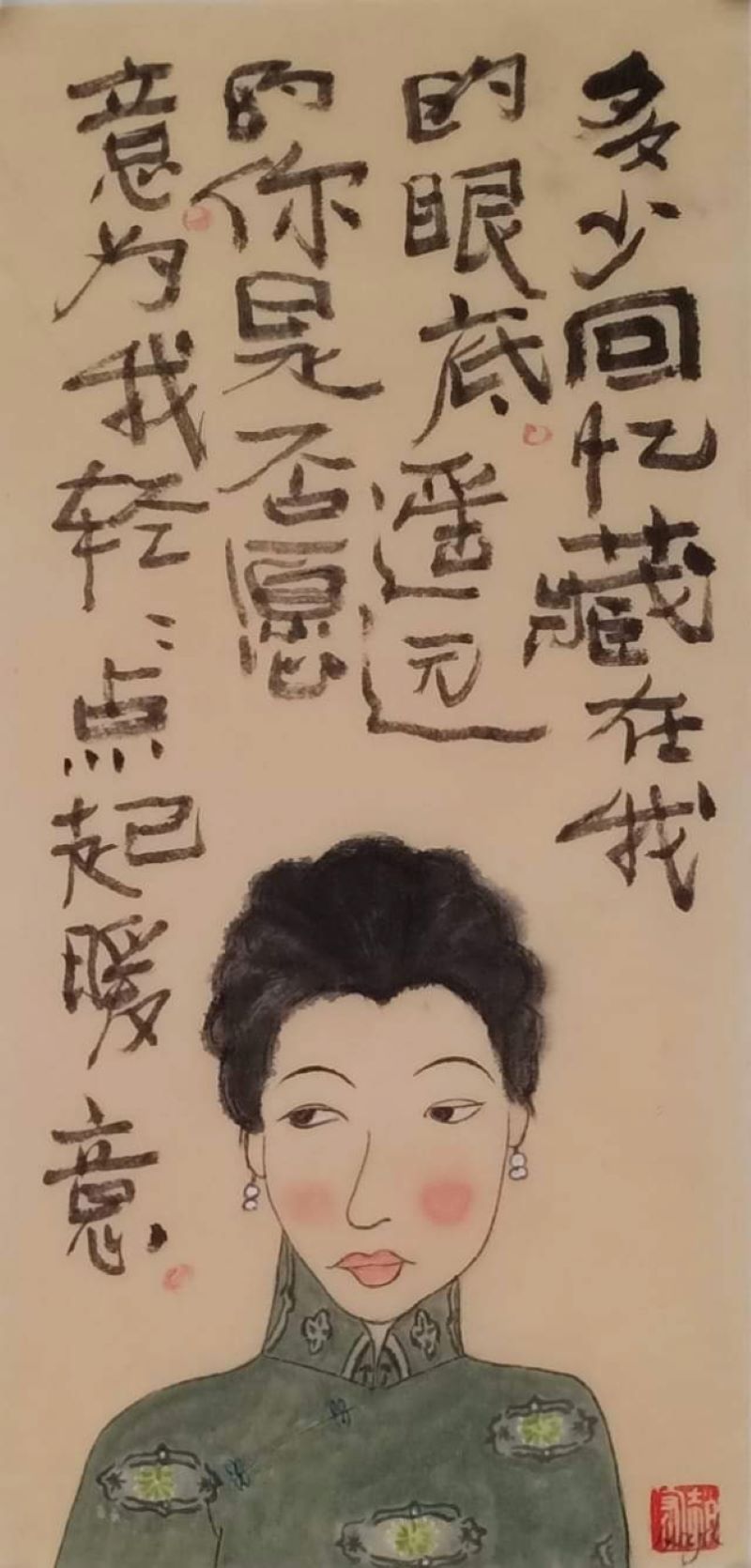

Fig. 7 Lloyd Zhao 赵宏, Duoshao huiyi 多少回忆, 2021, Chinese ink and colour pigment on rice paper, 34 x 17 cm. G Art Gallery, Singapore.

多少回忆藏在我的眼底,遥远的你是否愿意,为我轻轻点起暖意。

I have so many beautiful memories about you. I don’t know if you, who are far away from me now, would like to bring me some gentle warmth.

— Translated by Zhao Hong

In Duoshao huiyi 多少回忆 [Memories], Zhao Hong included an extract of Wang Jie’s 王杰 1989 song Shifou wozhen de yiwusuoyou 是否我真的一无所有 [If I really had nothing].

The artwork describes the physical distance and a prior relationship between two individuals. Feeling lonely during a state of hardship, one thinks fondly of the woman with whom one has many cherished memories.

The narrative suggests, presuming the perspective of a man who is the other in this artwork, that memories of a much-cherished woman still bind the man even though they are apart. Even in hardship, the man seeks the woman who had once enlivened his world and gave him happiness. – a companionship that is a comfort for him.

Womenfolk as a Sociological Conduit

While this selection of Zhao Hong’s New Literati artworks is by no means a definitive survey of Zhao’s xiaomeirentu 小美人图 [Images of Womenfolk] till date, these artworks do provide an insight into his perspective on the importance of womenfolk as a sociological conduit.

These highlighted artworks touch upon motherhood, subject of interest and memory, and empathy. Without the womenfolk, as portrayed in Zhao Hong’s artworks, the artworks and their texts would not make sense, akin to the absence of women in Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber.

The centrality of womenfolk in his artworks focuses on societal expectations and roles, familial connections, intergenerational histories and stories of families and between the people they are closest to – all of such qualities that have gained the most profound admiration and respect from Zhao Hong.

Hence, Zhao Hong’s xiaomeirentu becomes a celebration of the appreciation and reverence towards womenfolk’s sacrifice and virtues without prescribing patriarchal perspectives on them, and only the direct relevance and interconnectivity of womenfolk within our societies.

Inadvertently, Zhao Hong’s artistic approach towards womenfolk not only uniquely sets him apart from his New Literati peers that inspired him and also bestows upon him the rightful recognition that he is part of a global New Literati movement.

About the Curator

Vincent Lin is a curator and art historian based in Singapore and China. He currently holds the position of Curatorial Director at G Art Gallery, Singapore. With almost two decades of professional experience in Singapore’s visual arts and museum fields, he specialises in traditional, modern and contemporary Chinese ink art forms and modern art history in Singapore.

References

Chow, Rey. Woman and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading between West and East. Theory and History of Literature. Edited by Wlad Godzich and Jochen Schulte-Sasse. Vol. 75, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1991.

Chung, Priscilla Ching. Palace Women in the Northern Sung 960-1126. 2015 ed. 1981. Kindle edition.

Hereshatter, Gail. Women in China’s Long Twentieth Century. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2007.

Ko, Dorothy. Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Lee, Sangwha. “The Patriarchy in China: An Investigation of Public and Private Spheres.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 5, no. 1 (1999): 9-49. doi:10.1080/12259276.1999.11665840.

Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1990. 2013.

Teng, Jinhua Emma. “The Construction of the “Traditional Chinese Woman” in the Western Academy: A Critical Review.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 22, no. 1 (1996): 115-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3175043.

Wolf, Margery. Revolution Postponed: Women in Contemporary China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1985.

———. Women and the Family in Rural Taiwan. Stanford, California: Standford University Press, 1972.

Endnotes

[1]Pre-Modern China is defined as the Imperial dynasties of Qin dynasty (221—206 BC), Han dynasty (206 BC—AD 220), Three Kingdoms (AD 220—280), Jin dynasty (AD 266—420), Northern and Southern dynasties (AD 420—589), Sui dynasty (AD 581—618), Tang dynasty (AD 618—907), Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (AD 907—960), Song, Liao, Jin and Western Xia dynasties (AD 960—1279), Yuan dynasty (AD 1271—1368), Ming dynasty (AD 1368—1644) and Qing dynasty (AD 1644—1912).

[2] See Priscilla Ching Chung, Palace Women in the Northern Sung 960-1126, 2015 ed. (1981; repr., Kindle edition), 116-18. In her book, Chung argued that these Confucian teachings did not presume the universal subservience of women in Chinese society but allowed them responsibilities and privileges within their own spheres of class, and of specific women to specific men. However, this limited freedom did not easily allow women to transcend class and social spheres to replace men’s positions. It should also be pointed out that there were situations of exceptional women coming to power in Pre-Modern China, such as Tang dynasty Empress Dowager Wu Zetian 武則天 and Qing dynasty Empress Dowager Cixi 慈禧太后.

[3] While traditional roles of the woman centre on the inner sphere 内 of the family unit and men further their societal contributions in the patriarchal public outer sphere 外 in earlier periods of Chinese history, Chinese women’s roles have changed following shifting societal expectations and political ideologies – the dual-role aspect of Chinese women have increasingly become noteworthy in recent decades.

For further reading, see Rey Chow, Woman and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading between West and East, ed. Wlad Godzich and Jochen Schulte-Sasse, vol. 75, Theory and History of Literature (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1991); Gail Hereshatter, Women in China’s Long Twentieth Century (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2007); Margery Wolf, Women and the Family in Rural Taiwan (Stanford, California: Standford University Press, 1972); Revolution Postponed: Women in Contemporary China (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1985); Jinhua Emma Teng, “The Construction of the “Traditional Chinese Woman” in the Western Academy: A Critical Review,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 22, no. 1 (1996). http://www.jstor.org/stable/3175043; Sangwha Lee, “The Patriarchy in China: An Investigation of Public and Private Spheres,” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 5, no. 1 (1999). doi:10.1080/12259276.1999.11665840.

[4] Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China, 3rd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1990; repr., 2013), 104-08.

[5] Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1994).

[6] Professor Guo Xiaohuan is a Western art historian and PhD tutor based at the Chinese National Academy of Arts 中国艺术研究院. Professor Guo is also an established Chinese ink painter with profound insights into the arts.

[7] Today Art Museum (TAM) is a non-profit independent contemporary art museum founded in 2002 and is dedicated to promoting Chinese contemporary art and as a platform for dialogue and exploration of issues on the contemporary arts within a Chinese context.

[8] From the 1986 album Rang shijie chongman ai 让世界充满爱 [Let the world be filled with love] sung by a host of celebrity singers.

Vincent Lin

Curatorial Director

G Art Gallery

Originally posted on Weixin https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/WIGYaU0gac3r3j0d6OUhVQ